America’s democratic ideals regarding freedom and transparency, while noble, reveal a starkly different reality when it comes to background checks.

A study funded by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) found that having a criminal record lessens the chances of a job callback by 50%, and this penalty poses a color-based barrier as the lives of Black Americans are impacted far more than white applicants.1

These screenings – while intended to ensure safety and trust – disproportionately impact Black Americans’ access to employment, housing, and, ultimately, their well-being.

Despite this disconnect, many U.S. businesses, landlords, licensing boards and other entities rely on criminal background checks to establish a person’s eligibility, which only further perpetuates racial disparities.

What Do Background Checks Truly Reveal About Individuals?

In a world where background checks are the primary method of vetting a person’s eligibility to rent a home or obtain a job, a single negative mark on a person’s permanent record – whether they committed a crime or not – has lasting consequences.

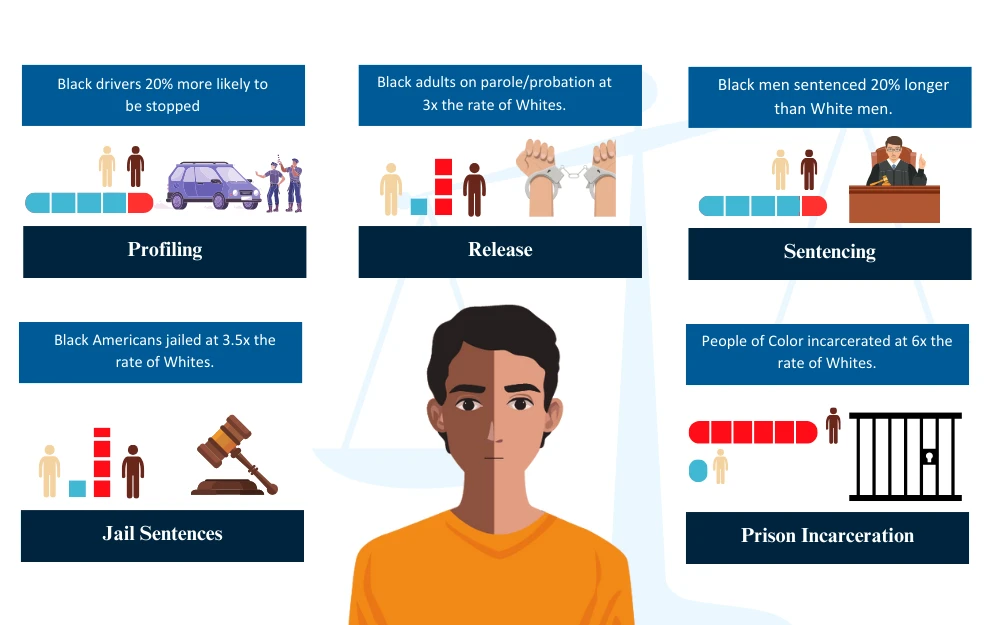

To add insult to injury, minority citizens and Black people specifically, are discriminated against throughout the entire criminal justice system, and any record created can negatively impact their housing and employment opportunities:

- Profiling: Black drivers are 20% more likely to be stopped than white drivers, adjusted for their share of the residential population.2

- Arrests Leading to Jail Sentences: Black Americans are incarcerated in jail at a rate of three and a half times (3.5x) higher than those of white people.3

- State Prison Incarceration: On average, people of color are locked up at a rate 6x those of white residents, a minimum of twice (2x) and a maximum of twelve times* (11.9x).4

- Sentencing: Black residents are less likely to receive a reduced plea than their white counterparts. Black men are, on average, sentenced to 20% longer than white men.5

- Release: Black adults are placed on parole and probation 3x more often than those of white adults.6 In other words, 1 in 23 Black adults are on parole or probation versus 1 in 81 white adults.

Confusion surrounding non-guilty verdicts, data brokers selling citizen data for a profit while government data is brushed under the rug, and a tiresome dispute process only adds fuel to the fire and further exacerbates the issue, creating a domino effect of inequality.

Should Decisions Made by Police Affect Employment & Hiring Opportunities?

Even though minorities are targeted more often, landlords and human resource departments nationwide use peoples’ permanent records to determine if they’re approved to rent a house or get a job.

Police officers’ discretions and whim-based decisions have shown to have serious effects on a person’s livelihood, but with public trust dwindling more and more with each instance of police brutality and murders like George Floyd’s, should the perspectives or opinions of police officers make or break someone’s future?

There’s no doubt that police play a valuable role in society and often risk their lives for the greater good of their fellow citizens, but given the general biases shown by countless studies, being arrested and charged certainly does not always equate to guilt.

Guilty Until Proven Innocent: When Transparency Backfires

In America, the “land of the free,” background screenings operate on the premise that citizens are guilty until proven innocent, meaning housing and employment prospects can be negatively impacted by a criminal record.

However, innocent people can be and frequently are wrongly arrested and prosecuted, and a few esoteric nuances surrounding public record screenings allow non-guilty verdicts to create a digital footprint.

- Arrests and non-guilty verdicts appear on background checks even when they don’t end in a conviction.

- Background checks may still reveal sealed and expunged records; this is because the erasure of these records is only available in some states, the process is lengthy and expensive, and the details of the records are sold by data brokers even after they’re removed.

While family members and loved ones may benefit from the transparency that arrest records provide, having unjust arrests that ended in non-guilty verdicts or that were erased lingering on a person’s record is prohibitive in more ways than one.

Fortunately, subjects of background checks can dispute inaccurate or outdated information if that’s why their application was denied; however, the appeal process can be drawn out and unfair, and the opportunity may be lost before the matter is resolved.

Inaccuracies & the Tiresome, Broken Dispute Process

Citizens’ permanent records are frequently mistaken for one another due to mismatching identities, fraud, simple filing mistakes, and many other reasons.

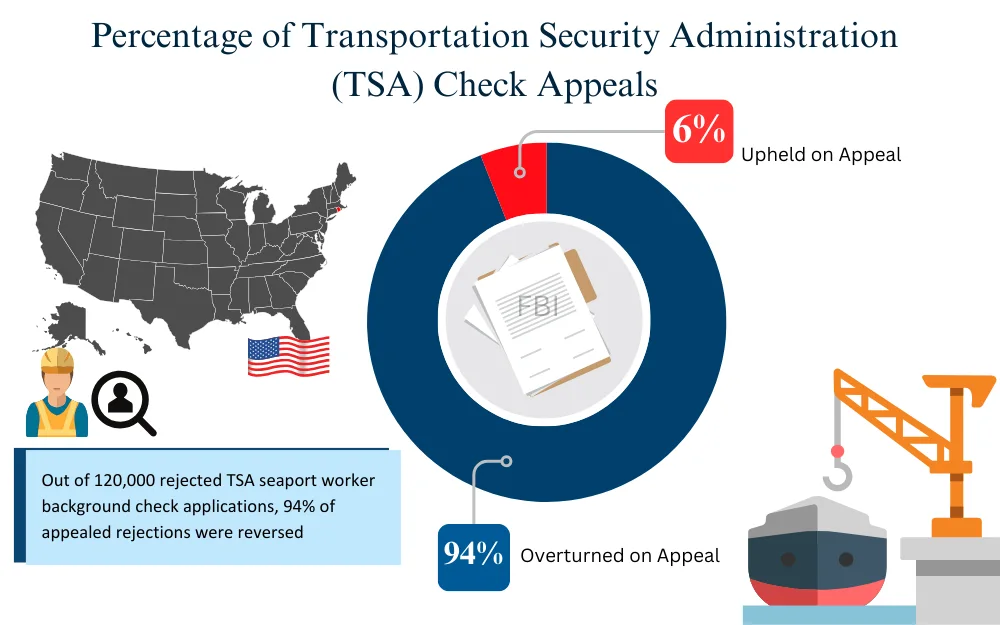

Illustrating the potential for inaccuracies and a faulty dispute process, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) required seaport workers to undergo a level 2 background check using FBI records, and out of 120,000 applications that were rejected and then disputed, 94% of appealed cases were overturned.

As seen above, these records become particularly important when establishing a person’s employment eligibility but also affect housing and licensing opportunities. While inaccurate records can be disputed, the process is nuanced, can take several months to resolve due to backlogs, and can lead to irrevocably lost opportunities.

For example, the United States Census Bureau hired over 1 million temporary workers and screened each through the FBI criminal database, which flagged applicants for arrests, regardless of the final disposition or outcome.

Applicants who had arrests reported had 30 days to submit court documents and challenge the record, but because the FBI data lacked clarity on whether the arrest led to a conviction and the onus to prove innocence was the applicants’ responsibility, the bureau’s approach appeared to use arrests of any reason to disqualify an applicant – irrespective of the relevance, significance, or final verdict.

Ultimately, this matter resulted in a class action lawsuit, resulting in a settlement, under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, where the flantiff’s argued that the screening device had a racially disproportionate effect on African American, Latino, and Native American applicants.7

How Cleared Charges’ Live On

In most states, arrests may appear on background checks for up to 7-10 years, even when the person is found not guilty and the charge results in a dropped or dismissed case.8

Probable cause can be a gray area, making it possible for people to be arrested based solely on the officers’ inclination and in the cases of unjust arrests, due factors outside of the individual’s control.

Of course, arrestees who are falsely accused individuals may go through the tedious and expensive process of sealing or expunging their records (if the state even allows it), but once something is on the internet, it lives on forever.

For example, data brokers harbor citizens’ personal information and sell it to consumers. Of course, people can request these sites to not sell their data but because there are several data sources, and many companies sell data to larger companies, requesting the removal of information from a small site doesn’t remove it from the primary data source.

Most of these sites will comply with data removal requests but they’re not consumer reporting agencies as defined by the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), which means employers cannot legally acquire public records from them to establish a person’s eligibility – but many do so regardless, even if unknowingly.

A Cause For Change: Putting It Into Perspective

This piece serves as a testament that arrests do not translate to guilt, criminal records serve as a poor indicator of a person’s character, and basing vital decisions on them perpetuates biased policing, ultimately undermining the chances and empowerment of the entire Black Community.

As shown here, the heart of racial disparities during background checks lies in a broken criminal justice system, disqualifying Black applicants from many housing, employment and other opportunities.

Landlords and Human Resource departments can improve their hiring practices by understanding the difficulties minorities face – from profiling, arrests, and disputing inaccuracies to barriers when applying for a house, apartment, job, or occupational license.

Through greater understanding comes empathy and compassion, allowing for a more rational and unbiased decision. The next time a background check report appears on the desk, keep these points in mind and ensure the applicant is fully considered, with or without a negative mark.

There is no better time than now to move away from reliance on the criminal justice system as a measure of a person’s worth and instead focus on equal opportunities from the ground up to eradicate systematic racism and biases.

References

1National Institute of Justice. (2012, June 14). In Search of a Job: Criminal Records as Barriers to Employment. Retrieved December 26, 2023, from <https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/search-job-criminal-records-barriers-employment>

2New York University. (2020, May 5). Research Shows Black Drivers More Likely to Be Stopped by Police. News Release. Retrieved December 26, 2023, from <https://www.nyu.edu/about/news-publications/news/2020/may/black-drivers-more-likely-to-be-stopped-by-police.html>

3U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2021, December). Jail Inmates in 2020 – Statistical Tables. Retrieved December 26, 2023, from <https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/ji20st.pdf>

4Prison Policy Initiative. (2023, September 27). Updated data and charts: Incarceration stats by race, ethnicity, and gender for all 50 states and D.C. Retrieved December 26, 2023, from <https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2023/09/27/updated_race_data/>

5Bureau of Justice Assistance U.S. Department of Justice. (2011, January 24). Plea and Charge Bargaining. Retrieved December 26, 2023, from <https://bja.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh186/files/media/document/PleaBargainingResearchSummary.pdf>

6Pew. (2018, December 6). Community Supervision Marked by Racial and Gender Disparities. Retrieved December 26, 2023, from <https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2018/12/06/community-supervision-marked-by-racial-and-gender-disparities>

7United States District Court | Southern District of New York. (2016, April). Executed Settlement Agreement with Exhibits. Retrieved December 26, 2023, from <https://ccrjustice.org/sites/default/files/attach/2016/04/Executed%20Settlement%20Agreement%20with%20Exhibits.pdf>

8Collateral Consequences Resource Center. (2020). 50-State Comparison: Limits on Use of Criminal Record in Employment, Licensing & Housing. Restoration of Rights Project. Retrieved December 26, 2023, from <https://ccresourcecenter.org/state-restoration-profiles/50-state-comparisoncomparison-of-criminal-records-in-licensing-and-employment/>